| 陈农摄影作品展

The Photography of Chen Nong

开幕时间:2007年10月20日15:00

展期:2007年10月20日至11月16日

电话:010-64381784/64375284

电邮: 798@798photogallery.cn

网址:www.798photogallery.cn

地址:北京朝阳区酒仙桥路4号798工厂内大山子艺术区百年印象摄影画廊

Opening time: Oct 20 3:00pm ,2007

Exhibition time: Oct 20,2007 –Nov 16, 2007

Tel: 8610-64381784/64375284

网址:www.798photogallery.cn

Add: No4,Jiu xianqiao road,Chao Yang district, BeiJing.

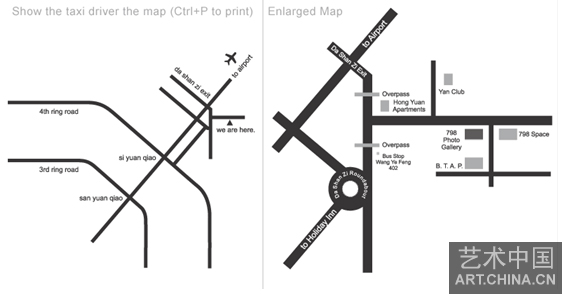

DIRECTION: 798 PHOTO GALLERY

陈农常在他的咖啡馆桌上画画,桌上放着巨大的照片,一个调色盘,一支大毛笔,一块抹布还有一只烟灰缸待在他旁边。他铺下一层颜色然后擦干,停下来聊聊天,混合一个新的色彩,在照片的空白处画下新的形状,然后再擦擦。几个小时内,他飞快顺畅的建立着一层层的色彩来不断完善他的作品。

每一系列的作品都会通过数月的时间来小心计划完善。首先是一个想法,一个地方或是主题:兵马俑,京剧,枪与荷叶,沙地,月球。在拍摄前的几个星期,陈农开始绘制制作纸衣服——用他画照片的笔和手法——快而轻松的笔触,同样的绿色,红色,蓝色,还有黄色。黑白照片隐匿了所有色彩只留下一些深深浅浅的痕迹。

每一次出行都是一次离开北京的假期, 陈农寻找着完美的处所 ,一帮朋友兼做模特或是助手带着衣服道具什么的。他已经在纸上绘制了草图,到达现场仍然飞快的设计新的适合语境的框架;作为一个摄影师——也作为一个画家——他胸有成竹。在拍摄过程中,很多时间画在模特的安排和衣服道具的准备上:一旦画面确定,他就用极少数的时间来拍摄。

当代中国视觉文化充满了历史符号重演——瞬间的辉煌,特定的时期,时代——有精良制作的史诗电影,也有粗制滥造的电视剧用着高价租来的服装。任何时候你打开电视都能看到无数的对30年代上海的描绘,全是旗袍和西装;调个频道你又到了60年代,一个有绿衣服和街上没有汽车的世界;再调台你又到了明或是清代:皇宫,或是武侠片。陈农的作品回应着这样的视觉环境,甚至是在他的作品制作方式上——像一个只有一个人的设计制作部,依据照片风格和他的想像力,做着独特的道具和服装。

陈农的很多作品把玩着中国历史图景——兵马俑站在月球上,还有一位宇航员(一个未来的出处,可能为将来的旅居月球给出一个中国计划);人物们穿得像是中国戏剧角色站在传统的木船上,带着步枪(纪念抗日战争的称呼);穿着清代服装的角色们站在故宫的前面,真的戴大盖帽穿制服的警卫站离一些距离;年轻人穿着同时代服装戴着动物头像面具,在古老的灰色胡同玩儿着。虽然很有趣,但陈农的照片不仅仅是图像玩笑,或历史的双语。

陈农的照片让人记忆起早期摄影风格和人物安排,角色们像是在行为中,但不移动;脸生硬或是沉重;眼睛没有睁开,盯着相机或是看向远方。观者刚开始注意到的不是历史感,(例如:京剧服和枪),而是一种沉重的感觉,一种不可追述的情怀。生硬的姿态,混浊的暗影,手工上色,这些元素使陈农的照片就如同跟周围的现实和历史的记忆若即若离的一个个梦境,也回应着我们对现实印象种种说不出来的内心感受。像梦一样,这些图片有种奇怪的气质,这种气质直接与陈农的工作方式有关——通过纸制服装和照片上色, 介于简单和奇异风格之间。20世纪早期的肖像摄影用的背景是彩绘的纸而服装都是真的。陈农确是带着纸衣服来到真的地方。但是当照片被洗出来并上色,就很难再将纸衣服从真的环境中区分出来。通过画他的衣服,陈农制造出一种幻想和真相,寻找他要的场景,调整他的模特,拍摄然后制作出照片再上色. Roland Barthes说每一长照片都有一个“出彩”,细节吸引着看者。在他看来,出采总是某一个真实的事物——老的鞋子,手的姿态。但在陈农的照片里,亮点不是某个真象,不是属于那个地方的真的东西,而是扁平的纸衣服和它们被绘制后的样子,一种短崭的令人信服的幻像让人瞬间跌入其中。总之,正是这种绘制服装和道具的方式(然后再绘制),给了陈农的作品这样的魅力。

Chen Nong paints standing over a table in his coffeeshop, a giant photograph draped over the table, a pallette of inks, a single battered calligraphy brush, a rag and an ashtray perched beside him. He lays a wash of color and wipes it dry, pauses to chat, mixes a new color, draws a shape in the blank spaces of the photograph, and wipes it away. He swiftly, casually builds the layered shades that define his work, finishing a painting in only a few hours.

Each photographic series is carefully planned over the course of several months. It

starts with an idea, a place or an object: clay tomb soldiers; opera costumes, guns and lotus leaves; sand dunes; the moon. For weeks before the shoot, Chen Nong paints paper costumes using the same brush and pallette he uses the paint the photographs—the same quick loose brushstrokes, and the same rich greens, reds, blues and yellows, colors that dissapear in but give depth to the black-and-white prints.

Every shoot is a journey out of Beijing, a group of friends serving as models and assistants carrying costumes and props, as Chen Nong searches for the perfect location.

He has already sketched several frames on paper, but he quickly designs new frames to fit the context. As a photographer—and as a painter—he is decisive. During the shoot, most of the time is spent positioning the models and arranging props and costumes: once the picture has been realized, he takes only a handful of shots.

Contemporary Chinese visual culture is full of historical reenactments—recreations of moments, periods, eras—ranging from highly “realistic” epic films produced with obsessive visual detail, to cheaply shot television dramas with costumes bought off-the-rack in department stores. Any time you turn on the television you see one of countless depictions of Shanghai in the thirties, all natty suits and qipaos; change the channel and you are in the 1960s, a world of padded green suits and streets without cars; change the channel again and you are in the Ming or Qing: a palace drama, or a martial-arts comedy sitcom. Chen Nong’s work echoes this visual environment, and even its mode of production. Like a one-man set-design department, he makes his own props and costumes, relying on reference photographs and his own imagination.

Many of Chen Nong’s photographs play with Chinese historical iconography—tomb soldiers stand on the moon with an astronaut (a reference to the future, perhaps, given China’s plans for moon travel in the next decades); figures dressed like Chinese opera characters stand in a traditional wooden boat, carrying rifles (calling to mind the war of Resistance against the Japanese); characters in Qing costumes sit in front of the Palace Museum, real guards in caps and suits visible in the distance; young people in contemporary street clothes, with giant animal heads, play in old grey hutongs. But though his work is playful, Chen Nong’s photographs are not merely iconographic jokes, or historical puns.

Chen Nong’s pictures bring to mind the staging and expressions of early glass-plate photography. The subjects are posed as if in action, but trying not to move; faces stiff or thoughtful; eyes unfocused, gazing at the camera or into the distance. The first thing the viewer notices is not the historical juxtaposition (i.e., opera costumes and AK47s), but the mood of grave nostalgia. The stiff poses, dark shadows, and painted-on-colors that make Chen Nong’s pictures reminiscent of early photographs also give them the quality of half-remembered dreams, cobbled together from the images that surround and permeate us. Like dreams, these pictures have a strange kind of integrity, an integrity which comes directly from Chen Nong’s process—the link between the easy, gestural style with which he paints the costumes, and applies layers of color to the finished photograph.

Unlike early twentieth century portrait photography, in which the backgrounds were painted paper and the costumes were real, Chen Nong takes paper clothes to real places. But when the photographs are printed and colored, it is hard to distinguish the paper costumes from the real surroundings, to tell what is painted before the photograph, what is painted on the photograph, and what is “really there”. Chen Nong builds layers of illusion and reality by painting his costumes, finding his locations, arranging his models, shooting and printing his photographs and coloring his prints. Roland Barthes describes “the punctum” of the photograph, the tiny detail of the photograph which hooks the viewer. For Barthes, this is always something real, an index of the unique historical moment of the picture—an old shoe, a gesture of the hand. In Chen Nong’s pictures, it is not the real bits which stick out—not the things tied to the real place—but the flatness of the paper costumes, and gestures with which they are painted, the way they fall just short of a convincing illusion. Above all, it is the painterly way the costumes and props are painted (and then repainted), which gives Chen Nong’s works such a haunting beauty.

|